The Chronicles of Narnia

First-edition covers, in order of publication |

|

|

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Prince Caspian The Voyage of the Dawn Treader The Silver Chair The Horse and His Boy The Magician's Nephew The Last Battle |

|

| Author | Clive Staples Lewis |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy Children's literature |

| Publisher | HarperTrophy |

| Published | 1950–1956 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) |

The Chronicles of Narnia is a series of seven fantasy novels for children written by C. S. Lewis. It is considered a classic of children's literature and is the author's best-known work, having sold over 100 million copies in 30 languages. Written by Lewis between 1949 and 1954, illustrated by Pauline Baynes and published in London between October 1950 and March 1956, The Chronicles of Narnia has been adapted several times, complete or in part, for radio, television, stage, and cinema. In addition to numerous traditional Christian themes, the series borrows characters and ideas from Greek and Roman mythology, as well as from traditional British and Irish fairy tales.

The Chronicles of Narnia presents the adventures of children who play central roles in the unfolding history of the fictional realm of Narnia, a place where animals talk, magic is common, and good battles evil. Each of the books (with the exception of The Horse and His Boy) features as its protagonists children from our world who are magically transported to Narnia, where they are called upon to help the Lion Aslan save Narnia.

Contents |

The series

The Chronicles of Narnia has been in continuous publication since 1954 and have sold over 100 million copies in 30 languages.[1][2][3]. Lewis was awarded the 1956 Carnegie Medal for The Last Battle, the final book in the Narnia series. The books were written by Lewis between 1949 and 1954 but were written in neither the order they were originally published nor in the chronological order in which they are currently presented.[4] The original illustrator was Pauline Baynes and her pen and ink drawings are still used in publication today. The seven books that make up The Chronicles of Narnia are presented here in the order in which they were originally published (see reading order below). Completion dates for the novels are English (Northern Hemisphere) seasons.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950)

.jpg)

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, completed in the Spring of 1949[4] and published by Geoffrey Bles in London on 16 October 1950, tells the story of four ordinary children: Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy Pevensie. They discover a wardrobe in Professor Digory Kirke's house that leads to the magical land of Narnia. The Pevensie children help Aslan, a talking lion, save Narnia from the evil White Witch, who has reigned over the kingdom of Narnia for a century of perpetual winter. The children become kings and queens of this new-found land and leave a legacy to be rediscovered in later books.

Prince Caspian: The Return to Narnia (1951)

.jpg)

Completed in the Fall of 1949 and published 15 October 1951, Prince Caspian: The Return to Narnia tells the story of the Pevensie children's second trip to Narnia. They are drawn back by the power of Susan's horn, blown by Prince Caspian to summon help in his hour of need. Narnia as they knew it is no more. Their castle is in ruins and all the dryads have retreated so far within themselves that only Aslan's magic can wake them. Caspian has fled into the woods to escape his uncle, Miraz, who had usurped the throne. The children set out once again to save Narnia.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952)

.jpg)

Completed in the Winter of 1950 and published on 15 September 1952, The Voyage of the ‘Dawn Treader’ returns Edmund and Lucy Pevensie, along with their priggish cousin, Eustace Scrubb, to Narnia. Once there, they join Caspian's voyage to find the seven lords who were banished when Miraz took over the throne. This perilous journey brings them face to face with many wonders and dangers as they sail toward Aslan's country at the end of the world.

The Silver Chair (1953)

.jpg)

Completed in the Spring of 1951 and published 7 September 1953, The Silver Chair is the first Narnia book without the Pevensie children. Instead, Aslan calls Eustace back to Narnia together with his classmate Jill Pole. There they are given four signs to aid in the search for Prince Rilian, Caspian's son, who disappeared after setting out ten years earlier to avenge his mother's death. Eustace and Jill, with the help of Puddleglum the Marsh-wiggle, face danger and betrayal before finding Rilian.

The Horse and His Boy (1954)

.jpg)

Completed in the Spring of 1950 and published 6 September 1954, The Horse and His Boy takes place during the reign of the Pevensies in Narnia, an era which begins and ends in the last chapter of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The story is about Bree, a talking horse, and a young boy named Shasta, both of whom have been held in bondage in Calormen. By chance, they meet each other and plan their return to Narnia and freedom. Along the way they meet Aravis and her talking horse Hwin who are also escaping to Narnia.

The Magician's Nephew (1955)

.jpg)

Completed in the Winter of 1954 and published by Bodley Head in London on 2 May 1955, the prequel The Magician's Nephew brings the reader back to the very beginning of Narnia where we learn how Aslan created the world and how evil first entered it. Digory Kirke and his friend Polly Plummer stumble into different worlds by experimenting with magic rings made by Digory's uncle, encounter Jadis (The White Witch) in the dying world of Charn, and witness the creation of Narnia. Many long-standing questions about Narnia are answered in the adventure that follows.

The Last Battle (1956)

.jpg)

Completed in the Spring of 1953 and published 4 September 1956, The Last Battle chronicles the end of the world of Narnia. Jill and Eustace return to save Narnia from Shift, an ape, who tricks Puzzle, a donkey, into impersonating the lion Aslan, precipitating a showdown between the Calormenes and King Tirian.

Reading order

Fans of the series often have strong opinions over the order in which the books should be read. Under dispute is the placement of two volumes, The Magician's Nephew and The Horse and His Boy, both of which take place significantly earlier than they were written, and which also fall somewhat outside the main story arc connecting the others. The "reading order" of the other five books is not disputed.

| Publication order | Chronological order | Written order | Final Completion order[4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe | The Magician's Nephew | The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe | The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe |

| Prince Caspian | The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe | Prince Caspian | Prince Caspian |

| The Voyage of the Dawn Treader | The Horse and His Boy | The Voyage of the Dawn Treader | The Voyage of the Dawn Treader |

| The Silver Chair | Prince Caspian | The Horse and His Boy | The Horse and His Boy |

| The Horse and His Boy | The Voyage of the Dawn Treader | The Silver Chair | The Silver Chair |

| The Magician's Nephew | The Silver Chair | The Magician's Nephew | The Last Battle |

| The Last Battle | The Last Battle | The Last Battle | The Magician's Nephew |

The books were not numbered when originally published. The first American publisher, Macmillan, numbered the books in the original publication order. When Harper Collins took over the series in 1994, the numbering was revised using the internal chronological order, as suggested by Lewis' stepson, Douglas Gresham. To make the case for his suggested order, Gresham quoted Lewis' 1957 reply to a letter from an American fan who was having an argument with his mother about the order:

I think I agree with your [chronological] order for reading the books more than with your mother's. The series was not planned beforehand as she thinks. When I wrote The Lion I did not know I was going to write any more. Then I wrote P. Caspian as a sequel and still didn't think there would be any more, and when I had done The Voyage I felt quite sure it would be the last, but I found I was wrong. So perhaps it does not matter very much in which order anyone read them. I’m not even sure that all the others were written in the same order in which they were published.[5]

In the Harper Collins adult editions of the books (2005), the publisher also uses this letter to assert Lewis' preference for the numbering they adopted by including this notice on the copyright page:

Although The Magician's Nephew was written several years after C. S. Lewis first began The Chronicles of Narnia, he wanted it to be read as the first book in the series. Harper Collins is happy to present these books in the order which Professor Lewis preferred.

However most scholars disagree with Harper Collins' decision and find the chronological order to be the least faithful to Lewis' intentions.[4] Scholars and readers who appreciate the original order believe that Lewis was simply being gracious to his youthful correspondent and that he could have changed the books' order in his lifetime had he so desired.[6] They maintain that much of the magic of Narnia comes from the way the world is gradually presented in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. They believe that the mysterious wardrobe, as a narrative device, is a much better introduction to Narnia than The Magician's Nephew — where the word "Narnia" appears in the first paragraph as something already familiar to the reader. Moreover, they say, it is clear from the texts themselves that The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was intended to be read first. When Aslan is first mentioned in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, for example, the narrator says that "None of the children knew who Aslan was, any more than you do" — which is nonsensical if one has already read The Magician's Nephew.[7] Other similar textual examples are also cited.[8]

Doris Meyer, author of C.S. Lewis in Context and Bareface: A guide to C.S. Lewis points out that rearranging the stories chronologically "lessens the impact of the individual stories" and "obscures the literary structures as a whole".[4] Peter Schakel devotes an entire chapter to this topic in his book Imagination and the Arts in C.S. Lewis: Journeying to Narnia and Other Worlds, and in Reading with the Heart: The Way into Narnia he writes:

- The only reason to read The Magician's Nephew first [...] is for the chronological order of events, and that, as every story teller knows, is quite unimportant as a reason. Often the early events in a sequence have a greater impact or effect as a flashback, told after later events which provide background and establish perspective. So it is [ ...] with the Chronicles. The artistry, the archetypes, and the pattern of Christian thought all make it preferable to read the books in the order of their publication.[7]

Christian parallels

- Specific Christian parallels may be found in the entries for individual books and characters.

C.S. Lewis was an adult convert to Christianity and had previously authored some works on Christian apologetics and fiction with Christian themes. However, he did not originally set out to incorporate Christian theological concepts into his Narnia stories, it is something that occurred as he wrote them. As he wrote in Of Other Worlds:

Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument, then collected information about child psychology and decided what age group I’d write for; then drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out 'allegories' to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn’t write in that way. It all began with images; a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn't anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord.

Lewis, an expert on the subject of allegory[9] and the author of The Allegory of Love, maintained that the books were not allegory, and preferred to call the Christian aspects of them "suppositional". This indicates Lewis' view of Narnia as a fictional parallel universe. As Lewis wrote in a letter to a Mrs Hook in December 1958:

If Aslan represented the immaterial Deity in the same way in which Giant Despair [a character in The Pilgrim's Progress] represents despair, he would be an allegorical figure. In reality, however, he is an invention giving an imaginary answer to the question, 'What might Christ become like if there really were a world like Narnia, and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?' This is not allegory at all.[10]

Although Lewis did not consider them allegorical, and did not set out to incorporate Christian themes in Wardrobe, he was not hesitant to point them out after the fact. In one of his last letters, written in March 1961, Lewis writes:

- Since Narnia is a world of Talking Beasts, I thought He [Christ] would become a Talking Beast there, as He became a man here. I pictured Him becoming a lion there because (a) the lion is supposed to be the king of beasts; (b) Christ is called "The Lion of Judah" in the Bible; (c) I'd been having strange dreams about lions when I began writing the work. The whole series works out like this.

-

- The Magician's Nephew tells the Creation and how evil entered Narnia.

- The Lion etc the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

- Prince Caspian restoration of the true religion after corruption.

- The Horse and His Boy the calling and conversion of a heathen.

- The Voyage of the "Dawn Treader" the spiritual life (especially in Reepicheep).

- The Silver Chair the continuing war with the powers of darkness

- The Last Battle the coming of the Antichrist (the Ape), the end of the world and the Last Judgement.[4]

With the release of the 2005 Disney film there was renewed interest in the Christian parallels found in the books. Some find them distasteful, while noting that they are easy to miss if you are not familiar with Christianity.[11] Alan Jacobs, author of The Narnian: The Life and Imagination of C. S. Lewis, implies that through these Christian aspects, Lewis becomes "a pawn in America's culture wars".[12] Some Christians see the Chronicles as excellent tools for Christian evangelism.[13] The subject of Christianity in the novels has become the focal point of many books. (See Further Reading below.)

Rev. Abraham Tucker pointed out that "While there are in the Narnia tales many clear parallels with Biblical events, they are far from precise, one-on-one parallels. (...) Aslan sacrifices himself in order to redeem Edmund, the Traitor, who is completely reformed and forgiven. That is as if the New Testament were to tell us that Jesus Christ redeemed Judas Iscariot and that Judas later became one of the Apostles. (...) There had been times in Christian history when Lewis might have been branded a heretic for far smaller creative innovations in theology."[14]

Influences on Narnia

Lewis' life

Lewis' early life has echoes within the Chronicles of Narnia. Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland in 1898, Lewis moved with his family to a large house on the edge of the city when he was seven. The house contained long hallways and empty rooms, and Lewis and his brother invented make-believe worlds while exploring their home – this influenced Lucy's discovery of Narnia in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.[15] Like Caspian and Rilian, Lewis lost his mother at an early age. Lewis also spent much of his youth in English boarding schools similar to those attended by the Pevensie children as well as Eustace Scrubb and Jill Pole. During World War II, many children were evacuated from London because of air raids. During this time, some of these children, including one named Lucy, his goddaughter, stayed with Lewis at his home in Oxford, just as the Pevensies stayed with the professor.[16]

Inklings

.jpg)

Lewis was the chief member of the Inklings, an informal literary discussion group in Oxford which at various times included the writers J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Lewis' brother W. H. Lewis, and Roger Lancelyn Green. Readings and discussions of the members' unfinished works were one of the main activities of the group when they met, usually on Thursday evenings, in C. S. Lewis' college rooms at Magdalen College. Some of the Narnia stories are thought to have been read to the Inklings for their appreciation and comment.

Influences from mythology and cosmology

The fauna of the series borrows from both Greek mythology and Germanic mythology. For example, centaurs originated in Greek myth, and dwarfs have origins in Germanic myth. Drew Trotter, president of the Center for Christian Study, noted that the producers of the film version of The Chronicles of Narnia felt that the books closely follow the archetypal pattern of the monomyth as detailed in Joseph Campbell's The Hero With a Thousand Faces.[17]

Lewis had also read widely in medieval Celtic literature, an influence reflected throughout the books, most strongly in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. The entire book imitates one of the immrama, a type of traditional medieval Irish tale in which the protagonists sail to a series of remarkable islands. Medieval Ireland also had a tradition of High Kings ruling over lesser kings and queens or princes, as in Narnia. Lewis' term "Cair," as in Cair Paravel, also mirrors the Welsh "Caer", "fortress" (appearing as Car- in the English versions of place names such as Cardiff (Welsh Caerdydd)). Reepicheep's small boat, the coracle, is also the traditional boat of the Celtic countries.

Some of the elements of the books are more generally medieval, such as the shape of the one-footed monopods or Dufflepuds in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, which reflects a type of people medieval sources claimed lived somewhere in the wondrous East.

In 2008 Michael Ward published Planet Narnia,[18] which proposed that each of the seven books related to one of the seven moving heavenly bodies or "planets" known in the Middle Ages, according to the Ptolemaic or Geocentric model of cosmology. Each of these heavenly bodies was believed in the Middle Ages to have certain attributes, and these attributes were deliberately (but secretly) used by Lewis to furnish elements of the stories of each book. "In The Lion [the Pevensie children] become monarchs under sovereign Jove; in The Dawn Treader they drink light under searching Sol; in Prince Caspian they harden under strong Mars; in The Silver Chair they learn obedience under subordinate Luna; in The Horse and His Boy they come to love poetry under eloquent Mercury; in The Magician's Nephew they gain life-giving fruit under fertile Venus; and in The Last Battle they suffer and die under chilling Saturn."[19] Lewis was known to have an interest in the literary symbolism of medieval and Renaissance astrology which is reflected far more overtly in other works of his such as his study of the Elizabethan world-view The Discarded Image, his early poetry, and more overt references to it in his science-fiction trilogy. Other Narnia scholars find Ward's assertion that Lewis intended the Chronicles as an embodiment of medieval astrology implausible.[4]

Name

The origin of the name Narnia is uncertain. According to Paul Ford's Companion to Narnia, there is no indication that Lewis was alluding to the ancient Italian Umbrian city Nequinium, which the conquering Romans renamed Narnia in 299 BC after the River Nar. However, since Lewis studied classics at Oxford, it is possible that he came across at least some of the seven or so references to Narnia in Latin literature.[4] There is also the possibility (but no solid evidence) that Lewis, who studied medieval and Renaissance literature, was aware of a reference to Lucia von Narnia ("Lucy of Narnia") in a 1501 German text, Wunderliche Geschichten von geistlichen Weybbildern ("Wondrous stories of monastic women") by Ercole d'Este.[20] There is no evidence of a link with Tolkien's Elvish (Sindarin) word narn, meaning a lay or poetic narrative, as in his posthumously published Narn i Chîn Húrin, though Lewis may have read or heard parts of this at meetings of the Inklings.

Narnia's influence on others

Influence on authors

A more recent British series of novels, Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, has been seen as a response to the Narnian books. The series by Pullman, a self-described atheist, wholly rejects the spiritual themes that permeate the Narnian series, but treats many of the same issues and introduces some similar character types (including talking animals).[21][22][23][24] Both His Dark Materials and the first published Narnia book open with a young girl hiding in a wardrobe.

Fantasy author Neil Gaiman wrote the 2004 short story The Problem of Susan,[25] in which an elderly woman, Professor Hastings, is depicted dealing with the grief and trauma of her entire family dying in a train crash. The woman's last name is not revealed, but she mentions her brother "Ed", and it is strongly implied that this is Susan Pevensie as an elderly woman. In the story Gaiman presents, in fictional form, a critique of Lewis' treatment of Susan. The Problem of Susan is written for an adult audience and deals with sexuality and violence.[26] Gaiman's young-adult horror novella Coraline has also been compared to The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. (Both books involve young girls traveling to magical worlds through doors in their new houses and having to fight evil with the help of talking animals) Additionally, Gaiman's Sandman graphic novel series features a Narnia-like "dream island" in its story arc entitled A Game of You.

In Katherine Paterson's book Bridge to Terabithia, one of the main characters, Leslie, tells the other main character, Jesse, of her love of C. S. Lewis' books, and mentions Narnia. Some people have accused Paterson of plagiarism, claiming that her book has taken the name of a Narnian island named "Terebinthia"; but Paterson has said that the reference was not deliberate.[27]

Science-fiction author Greg Egan's short story Oracle depicts a parallel universe with an author nicknamed "Jack" who has written novels about the fictional Kingdom of Nesica, and whose wife is dying of cancer. The story uses several Narnian allegories to explore issues of religion and faith versus science and knowledge.[28]

Influence on popular culture

As one would expect with any popular, long-lived work, references to The Chronicles of Narnia are relatively common in pop culture. References to the lion Aslan, travelling via wardrobe, and direct references to The Chronicles of Narnia occur in books, television, songs, games, and graphic novels.

The graphic novel The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (vol. 2, num. 1) makes multiple references to many famous works of fantasy literature including a text fragment referring to the apple tree from The Magician's Nephew. The next comic in the series mentions the possibility of making a wardrobe from the apple tree.

Popular television shows which refer to Narnia include multiple appearances of Aslan in South Park; in "Family Guy", Mr.Tumnus makes an appearance; and a character in Lost is named Charlotte Staples Lewis.

A computer game with an oblique reference to Narnia is Simon the Sorcerer which contains a scene in which the main character finds a stone table and calls it "perfect for troll meals and shaved lions".

See also Music.

Controversies

Gender stereotyping

C. S. Lewis and the Chronicles of Narnia have received various criticisms over the years, much of it by fellow authors. Most of the allegations of sexism centre around the description of Susan Pevensie in The Last Battle where Lewis characterises Susan as being "no longer a friend of Narnia" and interested "in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations".

J.K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter book series, has said:

There comes a point where Susan, who was the older girl, is lost to Narnia because she becomes interested in lipstick. She's become irreligious basically because she found sex, I have a big problem with that.[29]

Philip Pullman, author of the His Dark Materials trilogy and so fierce a critic of Lewis' work as to be dubbed "the anti-Lewis",[21][22][23][24] calls the Narnia stories "monumentally disparaging of women",[30] interpreting the Susan passages this way:

Susan, like Cinderella, is undergoing a transition from one phase of her life to another. Lewis didn't approve of that. He didn't like women in general, or sexuality at all, at least at the stage in his life when he wrote the Narnia books. He was frightened and appalled at the notion of wanting to grow up.[31]

Among others, fan-magazine editor Andrew Rilstone opposes this view, arguing that the "lipsticks, nylons and invitations" quote is taken out of context. They maintain that in The Last Battle, Susan is excluded from Narnia explicitly because she no longer believes in it. At the end of The Last Battle Susan is still alive; her ultimate fate is not specified in the series. Moreover, Susan's adulthood and sexual maturity are portrayed in a positive light in The Horse and His Boy, and therefore are argued to be unlikely reasons for her exclusion from Narnia.

Additionally, Lewis supporters cite the positive roles of women in the series, including Jill Pole in The Silver Chair, Aravis Tarkheena in The Horse and His Boy, Polly Plummer in The Magician's Nephew, and particularly Lucy Pevensie in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Jacobs asserts that Lucy is the most admirable of the human characters, and that, in general, the girls come off better than the boys through the stories.[12][32][33] Karin Fry, an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point, notes, in her contribution to The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy, that "the most sympathetic female characters in the Chronicles are consistently the ones who question the traditional roles of women and prove their worth to Aslan through actively engaging in the adventures just like the boys."[34] Fry goes on to say, however,

The characters have positive and negative things to say about both male and female characters, suggesting an equality between sexes. However, the problem is that many of the positive qualities of the female characters seem to be those by which they can rise above their femininity ... The superficial nature of stereotypical female interests is condemned.[34]

Race

In addition to sexism, Pullman also accused the Narnia series of fostering racism.[30][35] About alleged racism in The Horse and His Boy specifically, newspaper editor Kyrie O'Connor writes:

It's just too dreadful. While the book's storytelling virtues are enormous, you don't have to be a bluestocking of political correctness to find some of this fantasy anti-Arab, or anti-Eastern, or anti-Ottoman. With all its stereotypes, mostly played for belly laughs, there are moments you'd like to stuff this story back into its closet.[36]

The racism critique is based on a negative representation of other races, particularly the Calormenes. Novelist Philip Hensher and other critics regard the portrayal of Calormene culture as an attack on Islam.[37] Although the portrait of the Calormenes is coloured by European perceptions of Ottoman culture, the Calormene religion as portrayed by Lewis is polytheistic and bears little resemblance to Islam. Moreover, several Calormenes, notably Aravis in The Horse and his Boy and Emeth, the young Calormene soldier in The Last Battle, are portrayed favourably as brave and noble individuals and eventually enter Narnian heaven.

Paganism

Lewis has also received criticism from some Christians and Christian organizations who feel that The Chronicles of Narnia promotes "soft-sell paganism and occultism", because of the recurring pagan themes and the supposedly heretical depictions of Christ as an anthropomorphic lion. The Greek god Dionysus and the Maenads are depicted in a positive light (with the caveat that meeting them without Aslan around would not be safe), although they are generally considered distinctly pagan motifs. Even an animistic "River god" is portrayed in a positive light.[38][39] According to Josh Hurst of Christianity Today, "not only was Lewis hesitant to call his books Christian allegory, but the stories borrow just as much from pagan mythology as they do the Bible".[40]

Lewis himself believed that pagan mythology could act as a preparation for Christianity, both in history and in the imaginative life of an individual, and even suggested that modern man was in such a lamentable state that perhaps it was necessary "first to make people good pagans, and after that to make them Christians".[41] He also argued that imaginative enjoyment of (as opposed to belief in) classical mythology has been a feature of Christian culture through much of its history, and that European literature has always had three themes: the natural, the supernatural believed to be true (practiced religion), and the supernatural believed to be imaginary (mythology). Colin Duriez, author of three books on Lewis, suggests that Lewis believed that to reach a post-Christian culture one needed to employ pre-Christian ideas.[42] Lewis disliked modernism which he regarded as mechanized and sterile and cut off from natural ties to the world. By comparison, he had hardly any reservations about pre-Christian pagan culture. As Christian critics have pointed out,[43] Lewis disdained the non-religious agnostic character of modernity, but not the polytheistic character of pagan religion.[44]

Reception: influence of religious viewpoints

The initial critical reception was generally positive, and the series quickly became popular with children.[45] In the time since then, it has become clear that reaction to the stories, both positive and negative, cuts across religious viewpoints. Although some saw in the books potential proselytising material, others insisted that non-believing audiences could enjoy the books on their own merits.[46]

The Narnia books have a large Christian following, and are widely used to promote Christian ideas. Narnia 'tie-in' material is marketed directly to Christian, even to Sunday school, audiences.[47] As noted above, however, a number of Christians have criticized the series for including pagan imagery, or even for misrepresenting the Christian story[48] Christian authors who have criticised the books include fantasy author J.K. Rowling on ethical grounds (See Negative Responses) and literary critic John Goldthwaite in The Natural History of Make-Believe for elitism and snobbery in the books.

J. R. R. Tolkien was a close friend of Lewis, a fellow author and was instrumental in Lewis' own conversion to Christianity.[49] As members of the Inklings literary group the two often read and critiqued drafts of their work. Nonetheless, Tolkien was not enthusiastic about the Narnia stories, in part due to the eclectic elements of the mythology and their haphazard incorporation, in part because he disapproved of stories involving travel between real and imaginary worlds.[50] Though a Christian himself, Tolkien felt that fantasy should incorporate Christian values without resorting to the obvious allegory Lewis employed.[51]

Reaction from non-Christians has been mixed as well. Phillip Pullman has serious objections to the Narnia series linked to his anti-religious views. On the other hand, the books have appeared in neo-pagan reading lists[52] (by the Wiccan author Starhawk,[53] among others). Positive reviews of the books by authors who share few of Lewis' religious views can be found in Revisiting Narnia, edited by Shanna Caughey.

The producers of the 2005 film hoped to tap into the large religious audience revealed by the success of Mel Gibson's film The Passion of the Christ, and at the same time hoped to produce an adventure film that would appeal to secular audiences; but they (and the reviewers as well) worried about aspects of the story that could variously alienate both groups.[54]

Two full-length books examining Narnia from a non-religious point of view take diametrically opposite views of its literary merits. David Holbrook has written many psychoanalytic treatments of famous novelists, including Dickens, Lawrence, Lewis Carroll, and Ian Fleming. His 1991 book The Skeleton in the Wardrobe treats Narnia psychoanalytically, speculating that Lewis never recovered from the death of his mother and was frightened of adult female sexuality. He characterises the books as Lewis' failed attempt to work out many of his inner conflicts. Holbrook does give higher praise to The Magician's Nephew and Till We Have Faces (Lewis' reworking of the myth of Cupid and Psyche), as reflecting greater personal and moral maturity. Holbrook also plainly states his non-belief in Christianity.

In contrast to Holbrook, Laura Miller's The Magician's Book: A Skeptic's Guide to Narnia (2008) finds in the Narnia books a deep spiritual and moral meaning from a non-religious perspective. Blending autobiography and literary criticism, Miller (a co-founder of Salon.com) discusses how she resisted her Catholic upbringing as a child; she loved the Narnia books but felt betrayed when she discovered their Christian subtext. As an adult she found deep delight in the books, and decided that these works transcend their Christian elements. Ironically, a section in His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman, one of Narnia's severest critics, about how children acquire grace from innocence but adults from experience, had a profound influence on Miller's later appreciation of the Narnia books.[55]

The Narnian universe

Most of The Chronicles of Narnia take place in Lewis' constructed world of Narnia. The Narnian world itself is posited as one world in a multiverse of countless worlds including our own. Passage between these worlds is possible, though rare, and may be accomplished in various fashions. Narnia itself is described as populated by a wide variety of creatures, most of whom would be recognisable to those familiar with European mythologies and British fairy tales.

Inhabitants

- See also: Narnia creatures and Narnian characters

Lewis largely populates his stories with two distinct classes of inhabitants: people originating from the reader's own world and creatures created by the character Aslan and the descendants of these creatures. This is typical of works that involve parallel universes. The majority of characters from the reader's world serve as the protagonists of the various books, although some are only mentioned in passing. Those inhabitants that Lewis creates through the character Aslan are viewed, either positively or negatively, as diverse. Lewis does not limit himself to a single source; instead he borrows from many sources and adds a few more of his own to the mix.

Geography

- See also: Narnian places

The Chronicles of Narnia describes the world in which Narnia exists as one major landmass faced by "the Great Eastern Ocean". This ocean contains the islands explored in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. On the main landmass Lewis places the countries of Narnia, Archenland, Calormen, and Telmar, as well as a variety of other areas that are not described as countries. Lewis also provides glimpses of more fantastic locations that exist in and around the main world of Narnia, including an edge and an underworld.

There are several maps of the Narnian universe available, including what many consider the "official" one, a full-colour version published in 1972 by the books' illustrator, Pauline Baynes. This is currently out of print, although smaller copies can be found in the most recent HarperCollins 2006 hardcover edition of The Chronicles of Narnia. Two other maps have recently been produced following the popularity of the 2005 film The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. One, called the "Rose Map of Narnia", is based loosely on Baynes' map and has Narnian trivia printed on the reverse. The other, made in a monochromatic, archaic style reminiscent of maps of Tolkien's Middle-earth, is available in print and in an interactive version on the movie DVD. The latter map depicts only the country Narnia and not the rest of Lewis' world.

Cosmology

A recurring plot device in The Chronicles is the interaction between the various worlds that make up the Narnian multiverse. A variety of devices are used to initiate these cross-overs which generally serve to introduce characters to the land of Narnia. The Cosmology of Narnia is not as internally consistent as that of Lewis' contemporary Tolkien's Middle-earth, but suffices given the more fairy tale atmosphere of the work. During the course of the series we learn, generally in passing, that the world of Narnia is flat, geocentric, has stars with a different makeup than our own, and that the passage of time does not correspond directly to the passage of time in our world.

History

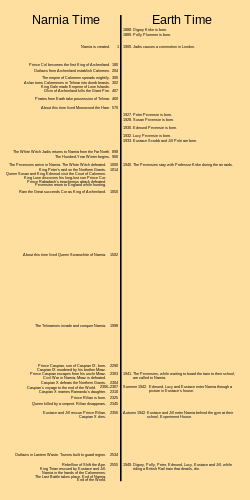

- See also: Narnian timeline

Lewis takes us through the entire life of the world of Narnia, showing us the process by which it was created, snapshots of life in Narnia as the history of the world unfolds, and how Narnia is ultimately destroyed. Not surprisingly in a children's series, children, usually from our world, play a prominent role in all of these events. The history of Narnia is generally broken up into the following periods: creation and the period shortly afterwards, the rule of the White Witch, the Golden Age, the invasion and rule of the Telmarines, their subsequent defeat by Caspian X, the rule of King Caspian and his descendants, and the destruction of Narnia. Like many stories, the narrative is not necessarily always presented in chronological order.

Narnia in other media

Television

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was first adapted for television in 1967. The ten episodes, each thirty minutes long, were directed by Helen Standage. The screenplay was written by Trevor Preston and unlike subsequent adaptations, it is currently unavailable to purchase for home viewing.

In 1979 The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was again adapted for television, this time as an animated special co-produced by Bill Meléndez (known for A Charlie Brown Christmas and other Peanuts specials) and the Children's Television Workshop (known for programs such as Sesame Street and The Electric Company). The screenplay was by David D. Connell. It won the Emmy award for Outstanding Animated Program that year. It was the first feature-length animated film ever made for television. For its release on British television, many of the characters' voices were re-recorded by British actors and actresses (including Leo McKern, Arthur Lowe and Sheila Hancock), but Stephen Thorne was the voice of "Aslan" in both the U.S. and British versions, and the voices of Peter Pevensie, Susan Pevensie, and Lucy Pevensie also remain the same.

From 1988–1990, parts of The Chronicles of Narnia were turned into four successful BBC television serials, The Chronicles of Narnia. They were nominated for a total of 14 awards, including an Emmy in the category of "Outstanding Children's Program". Only The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, Prince Caspian, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and The Silver Chair were filmed. The four serials were later edited into three feature-length films (combining Prince Caspian and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader) and released on VHS and DVD.

Radio

The critically acclaimed BBC Radio 4 dramatisation was produced in the 1980s. Collectively titled Tales of Narnia it covers the entire series and is approximately 15 hours long. The series was released in Great Britain on both audio cassette and CD by BBC Audiobooks.

In 1981, Sir Michael Hordern read abridged versions of the classic tales set to music from Marisa Robles, playing the harp, and Christopher Hyde-Smith, playing the flute. These were re-released in 1997 from Collins Audio. They have also been re-released in 2005 (ISBN 978-0-00-721153-1). http://www.harpercollinschildrensbooks.co.uk/books/default.aspx?id=33175

Between 1999 and 2002 Focus on the Family produced radio dramatisations of all 7 books through its Radio Theatre program. The production included a cast of over a hundred actors (including Paul Scofield as "The Storyteller" and David Suchet as "Aslan"), an original orchestral score and cinema-quality digital sound design. The total running time is slightly over 22 hours. Douglas Gresham, the stepson of C. S. Lewis, hosts the series. From the Focus on the Family website:

Between the lamp post and Cair Paravel on the Western Sea lies Narnia, a mystical land where animals hold the power of speech ... woodland fauns conspire with men ... dark forces, bent on conquest, gather at the world's rim to wage war against the realm's rightful king ... and the Great Lion Aslan is the only hope. Into this enchanted world comes a group of unlikely travellers. These ordinary boys and girls, when faced with peril, learn extraordinary lessons in courage, self-sacrifice, friendship and honour.[56]

Stage

In 1984, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was presented at London's Westminster Theatre, produced by Vanessa Ford Productions. The play, adapted by Glyn Robbins, was directed by Richard Williams and designed by Marty Flood; and was revived at Westminster and The Royalty Theatre and on tour until 1997. Productions of other Narnian tales were also presented, including The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1986), The Magician's Nephew (1988) and The Horse and His Boy (1990). Robbins's adaptations of the Narnian chronicles are available for production in the UK through Samuel French London.

In 1998 the Royal Shakespeare Company premiered The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The novel was adapted for the stage by Adrian Mitchell, with music by Shaun Davey. The musical was originally directed by Adrian Noble and designed by Anthony Ward, with the revival directed by Lucy Pitman-Wallace. The production was well received and ran during the holiday season from 1998 to 2002, at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford. The production also subsequently transferred to play limited engagements in London at the Barbican Theatre, and at Sadler's Wells. The London Evening Standard wrote:

...Lucy Pitman-Wallace's beautiful recreation of Adrian Noble's production evokes all the awe and mystery of this mythically complex tale, while never being too snooty to stoop to bracingly comic touches like outrageously camp reindeer or a beaver with a housework addiction... In our science and technology-dominated age, faith is increasingly insignificant — yet in this otherwise gloriously resonant production, it is possible to understand its allure.

Adrian Mitchell's adaptation later premiered in the US with the Tony award-winning Minneapolis Children's Theatre Company in 2000, and had its west-coast premiere with Seattle Children's Theatre playing the Christmas slot in its 2002–03 season (and was revived for the 2003–04 season). This adaptation is licensed for performance in the UK by Samuel French.

Other notable stage productions of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe have included commercial productions by Malcolm C. Cooke Productions in Australia (directed by Nadia Tass, and described by Douglas Gresham as the best production of the novel he had seen – starring Amanda Muggleton, Dennis Olsen, Meaghan Davies and Yolande Brown) and by Trumpets Theatre, one of the largest commercial theatres in the Philippines.

A streamlined version of the full-scale musical Narnia (adapted by Jules Tasca, with music by Thomas Tierney and lyrics by Ted Drachman) is currently touring the US with TheatreworksUSA. The full-scale and touring versions of the musical are licensed through Dramatic Publishing; which has also licensed adaptations of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by Joseph Robinette and The Magician's Nephew by Aurand Harris.

A licensed musical stage adaptation of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader made its world premiere in 1983 by Northwestern College (Minnesota) at the Totino Fine Arts Center. Script adaptation by Wayne Olson, with original music score by Kevin Norberg.

Theatrical productions of "The Chronicles of Narnia" have become popular with professional, community and youth theatres in recent years. A musical version of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe written specifically for performance by youth is available through Josef Weinberger.[57]

Film

Although Lewis did not want his books to be turned into films, it has been done four times, three of them for television (See Television). The BBC made television serial adaptations of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Prince Caspian, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Silver Chair. A film version of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, entitled The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, produced by Walden Media and distributed by Walt Disney Pictures was released in December 2005. Permission for films to be made was given by C. S. Lewis' stepson, Douglas Gresham. It was directed by Andrew Adamson. The screenplay was written by Ann Peacock. Principal photography for the film took place in Poland, the Czech Republic and New Zealand. Major Visual Effects Studios like Rhythm and Hues Studios, Sony Pictures Imageworks, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and many more worked on the VFX for the movie. The movie achieved critical and box-office success, reaching the Top 25 of all films released to that time (by revenue). Disney produced a sequel, The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian, released in May 2008 and grossed over $419 million worldwide. At the time of Caspian's release, Disney was already in pre-production on the next chapter, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. As of December 2008, Disney has announced it will not co-finance the third movie due to budgetary constraints although it appears that 20th Century Fox will continue the series.[58] Ernie Malik, unit publicist, confirmed that filming for this film started in Australia on 15 July 2009.[59]

Music

Themes or references to The Chronicles of Narnia have appeared in music. Narnia, a Swedish Christian power metal band whose songs are mainly about the Chronicles of Narnia or the Bible, features Aslan in all of their covers. Christian song writer Chris Rice in his song "Nonny" references Aslan and the adventures of the four rulers of Narnia.

A musical retelling of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe entitled The Roar of Love was released in 1980 by the contemporary Christian music group 2nd Chapter of Acts. American Christian rock band Relient K recorded "In like a Lion (Always Winter)". British hard-rock band Ten recorded "The Chronicles". Christian song writer TobyMac's song "New World", and Steve Hackett's song "Narnia" are all based on The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Singer/songwriter Bobby Wynn based his song "Voyage of the Dawn Treader" on the Chronicles of Narnia. In 1980 Star Song Communications released a compilation album in 1978 highlighting its stable of artists entitled Dawn Treader One that featured an image of Aslan on the left inside panel of the gatefold cover.

The band Phish have a song called "Prince Caspian" on their 1996 album Billy Breathes.

Finn Arild's debut album "Serendipity" includes two songs referring to Narnia: "Name and the Dance of the Monopods" and "Lantern Waste".

Audio books

The Chronicles of Narnia are all available on audiobook, read by Andrew Sachs. These were published by Chivers Children's' Audio Books.

In 1979, Caedmon Records released abridged versions of all seven books on records and cassettes, read by Ian Richardson (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and The Silver Chair), Claire Bloom (Prince Caspian and The Magician's Nephew), Anthony Quayle (The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Horse and his Boy) and Michael York (The Last Battle).

HarperAudio published the series on audiobook, read by British and Irish actors Michael York (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe), Lynn Redgrave (Prince Caspian), Derek Jacobi (The Voyage of the Dawn Treader), Jeremy Northam (The Silver Chair), Alex Jennings (The Horse and his Boy), Kenneth Branagh (The Magician's Nephew) and Patrick Stewart (The Last Battle).

Collins Audio also released the series on audiobook read by Sir Michael Hordern with original music composed and performed by Marisa Robles, as well as releasing a version read by the actor Tom Baker.

From 1998 to 2003 Focus on the Family Radio Theatre recorded all seven Chronicles of Narnia on CD. Each book had three CDs apart from The Magician's Nephew and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe which both had two CDs. They were released in association with The C.S. Lewis Company, with an introduction by Douglas Gresham. They used a cast of over one hundred actors, an original orchestral score, and digital sound design. The stars of the cast were Paul Scofield as the storyteller, David Suchet as Aslan, Elizabeth Counsell as the White Witch and Richard Suchet as Caspian X.

Games

In 1984, Word Publishing released Adventures in Narnia, a game developed by Lifeware. The game was intended to encourage positive values like self control and sacrifice. It incorporated physical elements such as cards and dice into the gameplay and was available on the Commodore 64.[60]

In November 2005, Buena Vista Games, a publishing label of Disney released videogame adaptations of the Walden Media/Walt Disney Pictures film. Versions were developed for most videogame platforms available at the time including Windows PC, Nintendo GameCube, Xbox, and PlayStation 2 (developed by the UK-based developer Traveller's Tales). A handheld version of the game was also developed by Griptonite Games for the Nintendo DS and Game Boy Advance.

Notes

- ↑ Kelly, Clint (2006). "Dear Mr. Lewis". Respone 29 (1). http://www.spu.edu/depts/uc/response/winter2k6/features/lewis.asp. Retrieved 22 September 2008. "The seven books of Narnia have sold more than 100 million copies in 30 languages, nearly 20 million in the last 10 years alone".

- ↑ Edward, Guthmann (11 December 2005). "'Narnia' tries to cash in on dual audience". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2005/12/11/NARNIA.TMP. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ↑ Glen H. GoodKnight. (2010). Narnia Editions & Translations. Last updated August 03, 2010

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Ford, Paul (2005). Companion to Narnia: Revised Edition. San Francisco: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-079127-6.

- ↑ Dorsett, Lyle; Marjorie Lamp Mead (ed.) (1995). C. S. Lewis: Letters to Children. Touchstone. ISBN 0684823721.

- ↑ Brady, Erik (1 December 2005). "A closer look at the world of Narnia". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/life/movies/news/2005-12-01-narnia-side_x.htm. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Schakel, Peter (1979). Reading with the Heart: The Way into Narnia. Grand Rapids: Erdmans. ISBN 0-8028-1814-5.

- ↑ Rilstone, Andrew. "What Order Should I Read the Narnia Books in (And Does It Matter?)". The Life and Opinions of Andrew Rilstone, Gentleman. http://web.archive.org/web/20051130010333/http://www.aslan.demon.co.uk/narnia.htm.

- ↑ Collins, Marjorie (1980). Academic American Encyclopedia. Aretê Pub. Co.. pp. 305. ISBN 0933880006.

- ↑ Martindale, Wayne; Root, Jerry. The Quotable Lewis.

- ↑ Toynbee, Polly (5 December 2005). "Narnia represents everything that is most hateful about religion". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2005/dec/05/cslewis.booksforchildrenandteenagers. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Jacobs, Alan (4 December 2005). "The professor, the Christian, and the storyteller". The Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2005/12/04/the_professor_the_christian_and_the_storyteller/. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ↑ Kent, Keri Wyatt (November 2005). "Talking Narnia to Your Neighbors". Today's Christian Woman 27 (6): 42. http://www.christianitytoday.com/tcw/2005/novdec/11.42.html. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ↑ Abraham Tucker, "Religion and Literature, Religion in Literature", New York, 1979 (Preface)

- ↑ Lewis, C.S. (1990). Surprised by Joy. Fount Paperbacks. pp. 14. ISBN 0006238157.

- ↑ Wilson, Tracy V. (7 December 2005). "How Narnia Works". HowStuffWorks. http://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/narnia.htm. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ↑ Trotter, Drew (11 November 2005). "What Did C. S. Lewis Mean, and Does It Matter?". Leadership U. http://www.leaderu.com/popculture/meaningandlewis-lwwpreview.html. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ↑ Michael Ward, Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis (Oxford University Press, 2008)

- ↑ Planet Narnia, By Michael Ward The Independent, 9 March 2008

- ↑ *Green "The recycled image" Times and Seasons, 1 June 2007

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Miller, "Far From Narnia The New Yorker, 26 December 2005

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Cathy Young, "A Secular Fantasy – The flawed but fascinating fiction of Philip Pullman", Reason Magazine (March 2008)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Peter Hitchens, "This is the most dangerous author in Britain", The Mail on Sunday (27 January 2002), p. 63

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Chattaway, Peter T. "Chronicles of Atheism, Christianity Today

- ↑ The story can be found in Flights: Extreme Visions of Fantasy Volume II (edited by Al Sarrantonio) and in the Gaiman collection Fragile Things.

- ↑ Gaiman: "The Problem of Susan", p. 151ff.

- ↑ Paterson, Katherine Paterson: On Her Own Words, p. 1

- ↑ Oracle Greg Egan, 12 November 2000

- ↑ *Lev Grossman J.K. Rowling Hogwarts And All TIME, 17 July 2005

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Ezard. "Narnia books attacked as racist and sexist" The Guardian, 3 June 2002

- ↑ Pullman "The Darkside of Narnia" The Cumberland River Lamppost, 2 September 2001

- ↑ "The Problem of Susan" RJ Anderson, 30 August 2005

- ↑ Lipstick on My Scholar" Andrew Rilstone, 30 November 2005

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Chapter 13: No Longer a Friend of Narnia: Gender in Narnia The Chronicles of Narnia and Philosophy: The Lion, the Witch and the Worldview Edited by Gregory Bassham and Jerry L. Walls; Open Court, Chicago and La Salle, Illinois, 2005

- ↑ "Pullman attacks Narnia film plans" BBC News, 16 October 2005

- ↑ Kyrie O'Connor, "5th Narnia book may not see big screen" IndyStar.com, 1 December 2005

- ↑ Philip Hensher, "Don't let your children go to Narnia: C. S. Lewis's books are racist and misogynist" Discovery Institute, 1 March 1999

- ↑ Chattaway, Peter T "Narnia 'baptizes' — and defends — pagan mythology" Canadian Christianity

- ↑ Kjos Narnia: Blending Truth and Myth Crossroad, December 2005

- ↑ Hurst, "Nine Minutes of Narnia"

- ↑ Moynihan (ed.) The Latin Letters of C. S. Lewis: C. S. Lewis and Don Giovanni Calabria

- ↑ C.S. Lewis, the Sneaky Pagan ChristianityToday, 1 June 2004

- ↑ "The paganism of Narnia". Canadian Christianity. http://www.canadianchristianity.com/cgi-bin/na.cgi?nationalupdates/051124narnia.

- ↑ See essay "Is Theism Important?" in God in the Dock by C.S.Lewis edited by Walter Hooper

- ↑ Into the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles p. 160 by David C. Downing

- ↑ The hope among Christian readers that Narnia could be conversion tool is mentioned in "Revisiting Narnia: Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis' Chronicles" by Shanna Caughey on p. 54. However, on p. 56 of "Encyclopedia of Allegorical Literature" by David Adams Leeming and Kathleen Morgan Drowne, it is argued that "They are by no means suitable only for Christian readers." A prominent Narnia online game site requests that Christians visiting the site not try to convert non-believers during game-chat. See Enter Narnia. The dispute over the relative prominence of the Christian fan-base is reflected in a [http://www.filibustercartoons.com/comics/20051227.gif cartoon at Filibustercartoons.com

- ↑ A Sunday school book entitled "A Christian Teacher’s Guide to Narnia" is offered for sale at "Christian Teachers guide to Narnia". http://www.tttools.com/A-Christian-Teachers-Guide-to-The-Chronicles-of-Narnia-2-5-Book_p_132-4590.html. The United Methodist Church has published its own Narnia curriculum as noted at "United Methodists find spiritual riches, tools, in 'Narnia'". FaithStreams.com. http://www.faithstreams.com/ME2/Sites/dirmod.asp?sid=5F4E345683D8492B9B56CBC49802F459&nm=Get+the+News&type=news&mod=News&mid=9A02E3B96F2A415ABC72CB5F516B4C10&SiteID=8E4FC92787CF4E8992A0D69DEFBEA620&tier=3&nid=16D0FB87115143F290CE976C98A0740F. Although Walden Media's Study Guides were not overtly Christian, they were marketed to Sunday schools by Movie Marketing.

- ↑ Trouble in Narnia: The Occult Side of C.S. Lewis Crossroad, February 2006; see also the Sayers biography, p. 419

- ↑ Carpenter, The Inklings, p.42-45. See also Lewis' own autobiography Surprised by Joy

- ↑ See Jack: A Life of C. S. Lewis by George Sayer, Lyle W. Dorsett p. 312-313

- ↑ On eclecticism, see Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship by Colin Duriez, p. 131; also The Inklings by Humphrey Carpenter, p. 224. On allegory, see Diana Glyer, The Company They Keep, p. 84, and Harold Bloom's edited anthology The Chronicles of Narnia, p. 140. Tolkien expresses his disapproval for stories involving travel between our world and fairy-tale worlds in his essay On Fairy-Stories.

- ↑ Amazon Suggested reading

- ↑ "How Narnia Made me a Witch". BeliefNet. http://www.beliefnet.com/Entertainment/Movies/The-Chronicles-Of-Narnia-Prince-Caspian/How-Narnia-Made-Me-A-Witch.aspx&page=2&id=118.

- ↑ On the dual concerns of the film makers, see See Edward, Guthmann (11 December 2005). "'Narnia' tries to appeal to the religious and secular". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/12/11/MNG0FG6AND1.DTL. Retrieved 22 September 2008. On talk of Christian appeal see "'Prince Caspian' walks tightrope for Christian fans". USAToday.com (USA Today). 19 May 2008. http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2008-05-16-narnia-christian-caspian_N.htm. Retrieved 25 May 2010. and 'Narnia' won't write off Christian values USA Today, 19 July 2001; The 'secular' appeal of the films is discussed in the San Francisco Chronicle's review Edward, Guthmann (11 December 2005). "Children open a door and step into an enchanted world of good and evil — the name of the place is 'Narnia'". SFGate (San Francisco Chronicle). http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/12/09/DDG9QG4FJS1.DTL. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ↑ Miller, p. 172

- ↑ Enter Narnia, Focus on the Family Radio Theatre, 2005

- ↑ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Guide to Musical Theatre

- ↑ Sanford, James (December 2008). "Disney No Longer Under Spell of Narnia". http://blog.mlive.com/james_sanford/2008/12/disney_is_no_longer_under_the.html.

- ↑ "The Mysterious Filming Date... Confirmed". Aslan's Country. 27 July 2009. http://www.aslanscountry.com/index.php/2009/07/27/the-mysterious-filming-date-confirmed/.

- ↑ Weiss, Bret. "Adventures in Narnia (synopsis)". All Game. http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=27618.

References

- Anderson, R.J. "The Problem of Susan", Parabolic Reflections 30 August 2005

- Chattaway, Peter T. "Narnia 'baptizes' — and defends — pagan mythology", Canadian Christianity, 2005

- Ezard, John. "Narnia books attacked as racist and sexist", The Guardian, 3 June 2002

- Gaiman, Neil, "The Problem of Susan", Flights: Extreme Visions of Fantasy Volume II (ed. by Al Sarrantonio), New American Library, New York, 2004, ISBN 0-451-46099-5

- Gopnik, Adam (2005). "Prisoner of Narnia". The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2005/11/21/051121crat_atlarge.

- Green, Jonathon "The recycled image", Times and Reasons, 2007

- Grossman, Lev J.K. Rowling Hogwarts And All, Time Vol. 166 – Issue=4 (25 July 2005)

- Goldthwaite, John, The Natural History of Make-believe: A Guide to the Principal Works of Britain, Europe and America: OUP 1996, ISBN 0195038061, ISBN 978-0195038064

- Hensher, Philip "Don't let your children go to Narnia: C. S. Lewis's books are racist and misogynist", The Independent, 4 December 1998

- Holbrook, David, The Skeleton in the Wardrobe: C. S. Lewis' Fantasies — A Phenomenological Study: Bucknell University Press, 1991, ISBN 0838751830, ISBN 978-0838751831

- Drama: 'Narnia' A Children's Musical, Stephen Holden, New York Times, 5 October 1986

- Hurst, Josh "Nine Minutes of Narnia", Christianity Today, 2005

- Jacobs, Tom (2004). Remembering a Master Mythologist and His Connection to Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara News-Press. ISBN. http://www.pacifica.edu/campbell/campbell04_news.html.

- Kjos, Berit Narnia: Blending Truth and Myth, Kjos Ministries, 2005

- Moynihan, Martin (ed.) The Latin Letters of C. S. Lewis: C. S. Lewis and Don Giovanni Calabria, St. Augustine's Press, 1009, ISBN 1890318345

- Martindale, Wayne; Root, Jerry The Quotable Lewis, Tyndale House, 1990, ISBN 0-8423-5115-9

- Miller, Laura "Far From Narnia, The New Yorker

- O'Connor, Kyrie "5th Narnia book may not see big screen" Houston Chronicle, 1 December 2005

- Meghan O'Rourke The Lion King: C. S. Lewis' Narnia isn't simply a Christian allegory, Meghan O'Rourke, Slate magazine, 9 December 2005

- Paterson, Katherine Katherine Paterson: On Her Own Words, Walden Media, 2006

- Pearce, Joseph Literary Giants, Literary Catholics, Ignatius Press, 2004, ISBN 1586170775

- Pullman, Philip "The Darkside of Narnia", The Guardian, 1 October 1998

- Ward, Michael Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis, Oxford University Press, 2008

Further reading

- Bruner, Kurt & Ware, Jim Finding God in the Land of Narnia, Tyndale House Publishers, 2005

- Bustard, Ned The Chronicles of Narnia Comprehension Guide, Veritas Press, 2004

- Duriez, Colin A Field Guide to Narnia. InterVarsity Press, 2004

- Downing, David Into the Wardrobe: C. S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles, Jossey-Bass, 2005

- Hein, Rolland Christian Mythmakers: C. S. Lewis, Madeleine L'Engle, J. R. R. Tolkien, George MacDonald, G.K. Chesterton, & Others Second Edition, Cornerstone Press Chicago, 2002, ISBN 094089548X

- Jacobs, Alan The Narnian: The Life and Imagination of C. S. Lewis, HarperSanFrancisco, 2005

- McIntosh, Kenneth Following Aslan: A Book of Devotions for Children, Anamchara Books, 2006

- Wagner, Richard C. S. Lewis & Narnia For Dummies, For Dummies, 2005

- Ward, Michael Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis, Oxford University Press, 2008

- A Guide for Using The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in the Classroom, Teacher Created Resources, 2000

- The Lion, Witch & Wardrobe Study Guide, Progeny Press, 1993

- The Magician's Nephew Study Guide, Progeny Press, 1997

- Prince Caspian Study Guide, Progeny Press, 2003

External links

- Harper Collins site for the books

- The secret of the wardrobe BBC News, 18 November 2005

- The Chronicles of Narnia Wiki

Related information

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||